Earning a college degree is generally considered to be the key to successful career pathways,1 a means for social mobility,2 and one of the only ways to remain competitive in the international marketplace of the 21st century.3 In the Seventh-day Adventist Church, many employees―including teachers and academic administrators―pursue additional credentialing to enhance their professional skills and to advance in their careers. However, in recent years, ethical questions have arisen related to various individuals’ academic integrity4 and the quality and legitimacy of academic degrees and other types of credentialing certain individuals have pursued.5 The purpose of this article is to address the issue of degree fraud, share the biblical basis regarding integrity as it relates to such situations, present ways to identify reputable colleges and accredited degree programs, and inform administrators and teachers, so they can better advise students about how to avoid enrolling in non-reputable institutions and programs.

In this article, we will use Teferra’s definition of Academic Fraud/Misconduct, which he describes as “manifest[ing] in multiple forms that include plagiarism, nepotism, corrupt recruitment and admission, cheating in exams, misrepresentation and falsifying of records, biased grading, bribery, conspiracy and collusion, among others.”6 However, this article will primarily focus on academic fraud―misrepresenting academic credentials that a person has earned from non-reputable colleges and unaccredited degree programs.

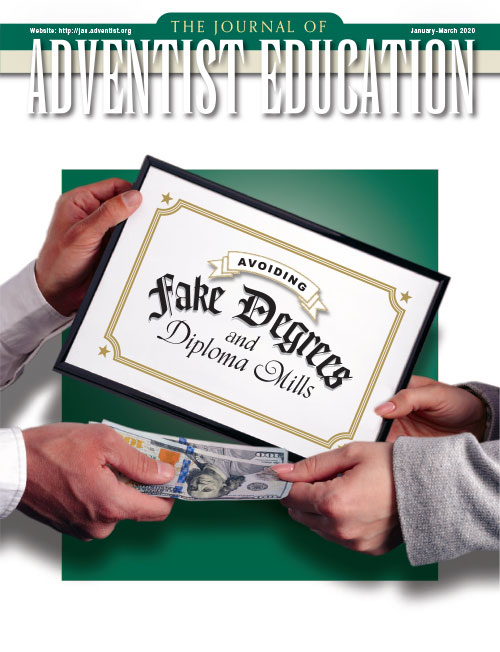

Many times, potential students are deceived and recruited to enroll in low-quality, non-accredited institutions, often referred to as “diploma mills.”7 In other cases, students and adult employees have knowingly enrolled and received credentials at such institutions8 with the intent of using these non-accredited, fake credentials/degrees to obtain employment, raises, and promotions. This goes against the moral values and principles that any professional should embrace. Adventist educators must exhibit more care in this regard because their choices are not only a reflection of their own personal integrity, but their actions also misrepresent the Christian community and standards of Jesus Christ. While Christians have an earthly mandate to ensure that they are being honest regarding academic integrity, they also have a higher ethical standard that they must uphold. Ellen White said, “No deviation from strict integrity can meet God's approval.”9 In the next section of this article, we will provide a synopsis of global examples of diploma fraud and discuss its impact on religious and secular institutions and industries.

A Global Perspective on Major Degree Issues

Problems with academic and degree fraud occur in all parts of the world.10 In the United States, accrediting agencies assess the quality of higher education and ensure that postsecondary institutions meet quality educational standards that foster professional learning environments.11 Degrees from universities with accredited educational programs are highly regarded by both students and employers.12

Even countries that have well-developed accreditation guidelines with clear standards for educational quality experience challenges with academic and degree fraud. This has led the International Center for Academic Integrity to sponsor an annual International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating (students paying others to write their papers).13 This event was created to raise awareness and focus attention on the issues of academic integrity and educational fraud worldwide.14

As of January 6, 2020, 263 Russian scientific journals agreed to retract 869 research articles, primarily for plagiarism. Other reasons included intentional duplication of content in multiple journals and unclear authorship.

In the Middle East and North Africa, in many cases, low-quality educational options and lax educational policies degrade students’ academic achievement and jeopardize their future career plans.15 For example, some Arab countries still lack educational policies that regulate e-learning programs. As a result, online degrees are negatively perceived by community members and employers, who do not consider them as valid employment credentials.16

Another major issue facing Arab countries today is the fake multi-million-dollar traditional (face-to-face/in classroom) degree industry.17 Today, more than ever, governments and societies are fighting degree forgery rings in Lebanon, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. In Lebanon, the Ministry of Higher Education and the Lebanese Military Intelligence Directorate recently commissioned fact-finding missions to investigate degree-forgery cases at two well-known private universities.18 Authorities suspect that university administrators and employees created a network that sold fake degrees to civilians and military personnel for US$9,000 each.19 According to Akoum,20 five soldiers were arrested for purchasing fake diplomas and using them to obtain military promotions.

Likewise, education authorities in Kuwait uncovered 400 fake university degrees in the fields of law and education.21 Following the raid, Kuwaiti investigators accused an Egyptian resident working at the Ministry of Higher Education of forging degrees for 50 people in government, private, and legal sectors in Kuwait.22 In a similar incident, eight professors at Kuwait’s Public Authority for Applied Education and Training were found guilty of possessing fake doctorate certificates they received from illusory universities in Greece.23 According to the culprits, the price of fake degrees in Kuwait depends on their level but is usually in the range of US$12,000.24

In Saudi Arabia, people with fake degrees still hold key positions in both public and private sectors.25 According to Al-Mulhim, the Saudi authorities have not taken any measures against the institutions issuing fake degrees. He wrote: “What is more distressing is the fact that even the so-called institutions, which award these fake certificates or degrees are also doing brisk business without hiding the true nature of their operations. . . . One of them is located in London and it openly cooperates with some elements in the education sector.”26

Another global issue in academic fraud is plagiarism and falsification of data.27 In 2012, Russia, at the direction of its president, launched an initiative to become a leader in scientific research. With this initiative came many monetary incentives and promises of promotions in rank to faculty who published their work. However, in January 2020, a staggering report by the Russian Academy of Sciences Commission for Countering the Falsification of Scientific Research found that 2,528 research articles in 541 Russian journals needed to be retracted. As of January 6, 2020, 263 Russian scientific journals had agreed to retract 869 research articles, primarily for plagiarism. Other reasons included intentional duplication of content in multiple journals and unclear authorship.28

Such cases are not limited to public education. Within the religious sector, breaches of academic integrity also occur. Within the Seventh-day Adventist Church, two recent cases documented by the local and international press alleged that several educational and church administrators committed academic fraud. In India, local authorities issued arrest warrants for three senior administrators at an Adventist university whom they alleged had obtained fake doctorate degrees.29 These allegations came as a shock to the constituents of the Adventist university, some of whom started questioning the legitimacy of the school because the accused administrators were supposed to uphold the ideals of the Adventist philosophy of education.30 Similarly, in South Africa, an elected church official was alleged to have hired a ghost writer for his doctoral dissertation. The subsequent fallout led to the individual’s resignation.31

Toward a Biblical Framework of Academic Integrity

The writers of this article believe that, as a Christian community, we should hold ourselves to the highest standard of integrity, and that there is a need to develop a biblically based framework for academic integrity, given the issues of academic fraud and cheating that can impact educational institutions globally at every level. Such a framework would provide guidance for those pursuing and seeking to obtain academic training and hold institutions offering academic degrees and credentialing accountable. Although the Bible does not explicitly provide examples of academic integrity as we would define it in modern times, the Scriptures do provide us with examples of integrity that align with the values that should be practiced in academic matters.

The foundation for such a framework should be based on biblical admonitions and examples of integrity within the Bible. One such example is demonstrated in the life of Joseph. In several instances, the Bible recounts how Joseph’s personal integrity guided his decisions, even when it seemed that taking the easy way out would have been benefited him (Genesis 37-39). Joseph’s main concern was to please God: “. . . How then could I do such a wicked thing and sin against God?” (Genesis 39:9, NIV).32

Another example can be found in the life of Job. Even though he questioned God (Job 3:11), was encouraged and tempted to curse God (chap. 2:9), and experienced total personal devastation and trauma, he did not waiver in his integrity and obedience. The Book of Daniel also provides several examples of God’s people displaying integrity under pressure: Daniel, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego refused to eat the king’s food and drink when exiled in Babylon (Daniel 1); Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were thrown into the fiery furnace for not bowing to a false god (Daniel 3); and Daniel was cast into a den or lions for praying to the God of heaven instead of the Babylonian king (Daniel 6).

Given that all humans are fallible and often have lapses in judgment, there is a need for redemption when people are uninformed and make mistakes. Unfortunately, however, many lapses in judgment are the product of an intentional decision to mislead others or illegitimately gain benefits for oneself; yet, even in such situations, redemption is still a possibility. A biblical example is Peter. In Matthew 26:69 to 75, despite having spent three years with Jesus, Peter denied knowing who Jesus was and declared that he was not a follower of the Galilean. Even though this was a major lapse in integrity, God empowered Peter to preach the gospel (Acts 9:36-43) and to powerfully testify that the Gentiles could be followers of Christ (Acts 10 and 11). The notion of redemption is key in these situations, particularly when individuals who have made mistakes express remorse. Yet, redemption must be balanced with other factors such as maintaining academic standards and appropriate consequences for fraud and dishonesty. The consequences of such actions can discredit the legitimacy of a degree and potentially harm the school, employer, clients, and the church.

To this end, a biblical framework of academic integrity should include the following:

For the student:

1. Embrace individual responsibility by practicing due diligence.

Scriptures such as Proverbs 11:14; 14:15; 19:2; and Matthew 7:7 (GNT)33 provide a biblical foundation for individuals to take responsibility for their actions, specifically in the area of conducting personal research. A person should exercise due diligence when investigating whether to enroll in an academic institution. This means ensuring that the degree, program, and/or institution is recognized and accredited by the appropriate accrediting bodies (church, state, and/or government). If the institution is unaccredited, find out why. It may be that the institution is new and just beginning the lengthy process toward becoming eligible for accreditation; that accreditation is not required (as is the case with some programs of study) although the institution is recognized and given permission by the government to operate; or that secular accreditation requirements demand that the institution compromise its system of beliefs, as is the case with some seminaries and Bible colleges.34 Also, take note of and investigate the accrediting body. Many schools that are actually diploma mills claim to be accredited, but often the entities under which they are accredited are not recognized by any legitimate source either within the government or a church organization.

2. Make a U-turn when appropriate if you uncover new, credible information.

When Christians uncover reliable information indicating that the direction they are going or the decisions they have made are incorrect or improper, they should immediately make appropriate changes. There is scriptural evidence that supports this type of action (see James 5:19 and 20 and 2 Peter 3:17 and 18). When people realize belatedly that they are pursuing a degree from an unaccredited institution or diploma mill, they should withdraw immediately and request a tuition refund. If individuals have obtained employment on the basis of enrolment in this type of degree program, the employer should be notified about the problem. The next step would be for the person to find a legitimate institution in which to pursue his or her academic training. The example of David’s willingness to be honest with Saul about the fact that he could not fight in Saul’s armor is a biblical example of the blessing of honesty (1 Samuel 17:39)—both to the individual and the institution. David likely would have lost the fight with Goliath and, in so doing, caused an Israelite defeat, if he had not had the courage to say, This armor is no suitable. If I can’t fight in what God has given me, then I am not the right person for this task.

3. Accept appropriate consequences for your actions.

Although we have argued the case for redemption, we recognize that actions have consequences. Even if someone did not intend to deceive or harm, damage may still have occurred, and restitution must be made. The Bible is replete with examples of leaders recognizing and acknowledging their wrongful deeds, yet God required them to still undergo discipline for their actions (see Proverbs 19:20 and Ecclesiastes 7:5). Moses is one such example. In Numbers 20:1 to 12, the Israelites had been wandering in the wilderness with no access to water and other food necessities. Moses and his brother Aaron asked God to provide the people with water. God told Moses to speak to a rock, and water would be provided for the people. However, Moses disobeyed by striking the rock with his staff. Because he was disobedient, he was not allowed to enter the Promised Land toward which he had led the people for 40 years.

In such cases, when consequences are enforced, a person who has committed the offense must acknowledge his or her wrong. The notions of grace and mercy should not be weaponized by a guilty person to escape appropriate consequences. People who commit such offenses should be humble, reflective, and apologetic regarding their actions. A commitment to honesty and integrity in future actions should be the stance of the person who is truly repentant.

For the institution/church:

1. Embrace and enforce the corporate responsibility of preserving high standards.

Adventist leaders and educators should avoid engaging in dishonest behavior or any actions that might create the perception of impropriety. Students must be taught the significance of academic integrity along with the consequences disregard for it can have on their personal and professional lives.

Scriptures such as 2 Corinthians 8:21 and Philippians 4:8 describe clear expectations of integrity to which Christians should adhere. In addition to the individual’s duty to conduct thorough research regarding an institution’s status, it is also the responsibility of a hiring organization and its administrators to conduct a careful investigation to make sure that all of their employees’ degrees or other forms of credentialing are legitimate. Both human-resource administrators and supervisors should conduct background checks on all employees to verify their academic credentials. Adventist universities should carefully scrutinize the qualifications submitted by applicants to make sure that degrees were earned from accredited schools, and that none of the documents are fraudulent.

2. Act with grace that offers the possibility of redemption.

Above all, if a person has obtained an illegitimate degree or other form of credentialing, the hiring organization should investigate and take appropriate action. If disciplinary action is necessary, it should be undertaken with the goal of balancing grace, redemption, and fairness. The Bible admonishes in 1 Peter 5:10, 2 Peter 3:9, and Colossians 3:13 that we are to extend forgiveness and love to one another. These principles should apply for individuals found to have intentionally misled or deceived the hiring organization, even if it means removal from a position due to their lack of appropriate credentials. God’s handling of Adam and Eve’s indiscretion at the tree of knowledge of good and evil offers a model for addressing the failures and frailties of our human condition and penchant for seeking to fulfill legitimate needs in illegitimate ways. We are reminded that even before Adam and Eve sinned, God had made provision through Christ to address the sin problem (Genesis 3). Similarly, effective leaders and organizations must be proactive rather than reactive in developing a process to address this problem of illegitimate degrees and credentialing before the problem occurs in their organization.

Adventist leaders and educators should avoid engaging in dishonest behavior or any actions that might create the perception of impropriety. Students must be taught the significance of academic integrity along with the consequences disregard for it can have on their personal and professional lives. The Book of Proverbs provides us with sound counsel in this regard: “people with integrity walk safely, but those who follow crooked paths will slip and fall” (chap. 10:9, NLT).35 It is important avoid being deceptive as Proverbs 11:3 states: “the integrity of the upright guides them, but the unfaithful are destroyed by their duplicity” (NIV). And given that ultimately, Adventist leaders and educators are accountable to God, they must be honest in all dealings: “the godly walk with integrity; blessed are their children who follow them” (Proverbs 20:7, NLT).

How to Avoid Non-Reputable Postsecondary Institutions

Higher education institutions that provide fraudulent degrees are often referred to as diploma mills.36 These schools offer low-quality educational programs and are not regulated by government or private quality-assurance organizations. All teachers, administrators, and students are encouraged to investigate whether the school in which they plan to enroll is accredited before applying for enrollment. Failure to attend accredited schools and enroll in legitimate programs will lead to unrecognized degrees that governments, graduate programs, and employers refuse to accept.37 According to the U.S. Department of Education,38 professionals and students pursuing postsecondary degrees or certifications can avoid fraudulent organizations by considering the following features as red flags:

- The school offers fast-track degree programs, offers credit for life experiences, and requires fewer credit hours than similar programs offered by accredited universities.

- Tuition fees are charged on per-degree basis rather than on the basis of credit hours earned by students.

- Financial discounts or incentives offered for individuals willing to pursue more than one major.

- University Websites that cite non-existent accreditation bodies are predatory.

- If faculty profiles and qualifications are not disclosed, this indicates a lack of institutional accountability.

- The university lacks an actual physical location. Vague addresses or addresses with nothing but post office box numbers or suite numbers are further evidence that it is a fake university.

- Scholarship scams that ask students for payment in advance are questionable.

- University Websites that end in .com are likely to be connected to a commercial institution whose primary motive is financial profit. Most legitimate universities end in .edu, although some may also have a country code added, while others may not have .edu at all but rather an organizational URL. Also, Websites with missing links, corrupted files that do not open properly, misspellings, and grammatical errors are likely proof of deceptive practices. Course descriptions and promotional materials online often contain misspellings and grammatical errors.

The above recommendations can assist anyone investigating the credibility of a post-secondary institution. In the next section, we will provide recommendations to help administrators investigate the legitimacy of diplomas and credentials.

Countering Academic Fraud: Recommendations for Administrators

Verifying the legitimacy of diplomas and credentials is the responsibility of every academic institution and organization. The academic registrar or human resources officer should consider the following when vetting the credentials of a potential student or employee:

1. Sequence. Traditionally, a high school diploma or general-education diploma (GED) precedes a bachelor’s degree, and a bachelor’s degree is typically earned before a Master’s or doctoral degree. An out-of-sequence listing of degrees is a red flag, as is the absence of any preceding degree. For example, an applicant’s moving from a bachelor’s to a doctorate without evidence of having earned a Master’s degree should raise suspicion, as would the possession of a Master’s degree and/or doctorate without proof of a bachelor’s degree and/or high school diploma.

2. Time. An undergraduate degree typically requires three to four years to complete, a Master’s one to two years, and a doctorate usually requires three or more years. A degree earned in a short time span―or several degrees earned over a short time period―indicates that something may be amiss.

3. Location. With the growth of online and distance education, an individual can enroll in an institution that is some distance away from his or her home. If this is the case, check and make sure the institution listed is an accredited distance-learning program.

4. Familiar-sounding but not-quite-right names. Many diploma mills tend to use names that appear very similar to those of legitimate institutions. If the school’s name seems vaguely familiar but not quite right, this warrants investigation. The same caution applies for foreign colleges and universities. If the individual lists a school outside of the country in which he or she currently resides, and there is no evidence of his or her having lived in that country, this should be verified.39

Here are some suggestions for verifying the legitimacy of documents and engaging in due diligence to identify fraudulent credentials:

1. Contact the institution directly. Ask to speak with the academic records department. The school’s registrar should be able to confirm factual information such as when the individual attended the school (dates), what degree he or she earned, and should be able to provide transcripts once the applicant has requested and paid for the service. Note that more and more diploma mills are offering “verification services” such as a live person to answer inquiries by telephone and mail out verification information. So, more needs to be done beyond just calling and talking to someone.

2. Do an online search. Concerted effort must be devoted to researching the institution and verifying the diplomas/degrees earned. Just because a school looks and sounds legitimate does not mean that it is. Check to see if the institution is accredited by a recognized accrediting agency. Does the school have the appropriate national, regional, or programmatic accreditation? Does the name of the school appear online connected with lawsuits or questionable situations? When perusing the school’s Website, look at areas such as tuition (is it charged by the degree or by credits, course, or semester, as is typical in most legitimate schools?). What are the degree requirements? Are there specific program requirements, or is the primary requirement life and work experience? Call surrounding schools, and ask if transfer credits from the institution under review are accepted by them. This may provide more information or help to alert other neighboring institutions.

3. Request verification from the potential student or employee. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the potential student or employee to provide verification that the diplomas and degrees he or she is presenting were earned from an accredited institution. This is especially so if these credentials are requirements for financial assistance or positions the person will hold.40

Fighting academic corruption requires vigilance on all fronts (see Figure 1). Academic institutions and hiring organizations must have in place strong verification and authentication policies that will help them uncover fraud. This includes oversight and training of personnel, purchasing and implementing the use of software products that can identify and track red flags, and an overall commitment to preserving and upholding high standards.

Conclusion

The choice of an academic institution in which to study is a very important decision in a person’s life. A significant amount of time and financial resources are invested in a high-quality education. Therefore, it is vitally important that teachers and administrators carefully research the institutions in which they plan to pursue advanced studies. Educators can also actively provide the students they serve with resources to assist them in doing the same thing as they prepare to continue their studies. Armed with a framework to guide decision-making and reminded of typical red flags, informed choices are possible. It is the hope of the authors of this article that the information provided will empower individuals to make sound choices when selecting academic institutions and pursuing academic credentials and degrees.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended citation:

Sydney Freeman, Jr., Ibrahim Karkouti, and Ty-Ron M. O. Douglas, “Avoiding Fake Degrees From Diploma Mills: Recommendations for Educators and Academic Administrators,” The Journal of Adventist Education 82:1 (January-March 2020): 4-11.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- Kimberly Joyce Branch, “Access to Higher Education for Black Men: A Narrative Perspective.” Unpublished Master’s thesis, Eastern Illinois University, 2007; Jennifer Merritt, “The Value of a College Degree, Around the Globe,” Linked in (June 11, 2013): https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20130611153023-20195722-the-value-of-a-college-degree-around-the-globe/

- Ibrahim M. Karkouti, “Black Students’ Educational Experiences in Predominantly White Universities: A Review of the Related Literature,” College Student Journal 50:1 (March 2016): 59-70.

- Ibrahim M. Karkouti, “Work and Unemployment in Youth (Egypt).” In Bloomsbury Education and Childhood Studies (London: Bloomsbury, 2019): http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350996281.0027; Ann-Marie Bathmaker et al., Higher Education, Social Class and Social Mobility: The Degree Generation (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); U.S. Department of Education, The State of Racial Diversity in the Educator Workforce (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2016): https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/highered/racial-diversity/state-racial-diversity-workforce.pdf .

- Adventist News Network, “Paul Ratsara Resigns as SID President,” Adventist Review (May 31, 2016): https://www.adventistreview.org/church-news/story4047-paul-ratsara-resigns-as-sid-president.

- Ardhra Nair, “Police Look for Three Spicer Officials in Fake Degree Case,” The Times of India (May 20, 2018): https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/pune/police-look-for-three-spicer-officials-in-fake-degree-case/articleshow/64240016.cms.

- Damtew Teferra, “The Need for Action in an Era of Academic Fraud,” University World News (September 21, 2018): https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20180918104541112.

- Creola Johnson, “Credentialism and the Proliferation of Fake Degrees: The Employer Pretends to Need a Degree; The Employee Pretends to Have One,” Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal 23:2 (August 2006): 269-343.

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC), “Avoid Fake-Degree Burns by Researching Academic Credentials” (January 2005): https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/avoid-fake-degree-burns-researching-academic-credentials.

- Ellen G. White, Patriarchs and Prophets (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald, 1896), 130.

- Bernie Bleske, “Think American Admission’s Fraud is Bad? International Academic Fraud Is Likely Worse” Age of Awareness (March 13, 2019): https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/think-american-admissions-fraud-is-bad-6982453eafe3.

- Dave Anderson, “Choosing a College or University in the USA,” Study USA (Updated April 25, 2019): https://www.studyusa.com/en/a/2/choosing-a-college-or-a-university-in-the-usa.

- Carly Minsky, “What Impact Does University Reputation Have on Students?” The World University Rankings (Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University) (May 4, 2016): https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/what-impact-does-university-reputation-have-students.

- International Center for Academic Integrity, “4th International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating” (2019): https://academicintegrity.org/day-against-contract-cheating/. Contract cheating is a term used for situations where students pay others to complete academic work such as write papers, conduct research, or complete assignments and projects. Additional issues include admissions and examination fraud, bribery, essay mills and plagiarism, forged degrees, and much more.

- Stefan Trines, “Academic Fraud, Corruption, and Implications for Credential Assessment,” World Education News and Reviews (December 2017): https://wenr.wes.org/2017/12/academic-fraud-corruption-and-implications-for-credential-assessment.

- David W. Chapman and Suzanne L. Miric, “Education Quality in the Middle East,” International Review of Education 55:4 (July 2009): 311-344. doi:10.1007/s11159-009-9132-5; Samar Farah and Soraya Benchiba, Investing in Tomorrow’s Talent: A Study on the College and Career Readiness of Arab Youth (Dubai, UAE: Abdulla Al Ghurair Foundation for Education, 2018); World Bank, Education Attainment in the Middle East and North Africa (2014): http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/284911468273894826/pdf/WPS7127.pdf.

- Ibrahim M. Karkouti, “University Faculty Members’ Perceptions of the Factors That Facilitate Technology Integration Into Their Instruction: An Exploratory Case Study in Qatar.” Unpublished EdD diss., University of Hartford, 2016.

- Courtney Trenwith, “UAE Residents Caught in Million-dollar, Global Fake Degree Scam,” Arabian Business (May 19, 2015): https://www.arabianbusiness.com/uae-residents-caught-in-million-dollar-global-fake-degree-scam-593253.html.

- Caroline Akoum, “Lebanon Launches Investigation Into Fake Military Diplomas,” ASHARQ AL-AWSAT (July 29, 2018): https://aawsat.com/english/home/article/1346776/lebanon-launches-investigation-fake-military-diplomas.

- Edmond Sassine, “Corruption Scandal Hits Universities: Degrees Sold for $9,000,” LBC International (July 23, 2018): https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/d/news-bulletin-reports/391353/report-corruption-scandal-hits-universities-degree/en.

- Ibid.

- “Kuwait Uncovers 400 Fake University Degrees,” Middle East Monitor (July 23, 2018): https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180723-kuwait-uncovers-400-fake-university-degrees/.

- Jaber Al-Hamoud and Munaif Nayef Al-Seyassah Staff and Agencies, “50 Kuwaitis Holding Forged University Degrees,” Arab Times (July 19, 2018): http://www.arabtimesonline.com/news/50-kuwaitis-holding-forged-university-degrees/.

- “Some Fake Doctorate Holders Employees of PAAET and KU,” Arab Times (July 14, 2017): http://www.arabtimesonline.com/news/fake-doctorate-holders-employees-paaet-ku/.

- Ibid.

- Abdulateef Al-Mulhim, “Fake Degree Is a Serious Matter,” Arab News (March 16, 2015): http://www.arabnews.com/columns/news/718806.

- Ibid., para. 3.

- Ben R. Martin, “Whither Research Integrity? Plagiarism, Self-plagiarism and Coercive Citation in an Age of Research Assessment,” Research Policy 42:5 (June 2013): 1,005-1,014. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.03.011.

- Robyn Dixon, “Amid Push for Russian Scientific Prestige, Academic Fraud Rampant,” The Washington Post (January 19, 2020); Dalmeet Singh Chawla, “Russian Journals Retract More Than 800 Papers After ‘Bombshell’ Investigation,” Science 367:6474 (January 8, 2020): https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/01/russian-journals-retract-more-800-papers-after-bombshell-investigation.

- Nair, “Police Look for Three Spicer Officials in Fake Degree Case.”

- Ibid.

- Adventist News Network, “Ratsara Resigns as SID President.”

- Genesis 39:9, New International Version (NIV). Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.®Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

- Proverbs 11:14, 14:15, 19:2; Matthew 7:7. Good News Translation (GNT). Copyright © 1992 by American Bible Society.

- Thomas Bartlett, “A College That’s Strictly Different,” The Chronicle of Higher Education 52:29 (March 2006): A20: https://web.archive.org/web/20090422041405/http://chronicle.com/free/v52/i29/29a04001.htm.

- New Living Translation(NLT). Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2015 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.

- U.S. Department of Education, “Diploma Mills and Accreditation―Diploma Mills” (December 23, 2009): https://www2.ed.gov/students/prep/college/diplomamills/diploma-mills.html.

- Alan Contreras and George Gollin, “The Real and the Fake Degree and Diploma Mills,” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 41:2 (2009): 36-43.

- Ibid.; U.S. Department of Education, “Diploma Mills and Accreditation―Diploma Mills.”

- U.S. Federal Trade Commission, FTC Facts for Business, “Avoid Fake-Degree Burns by Researching Academic Credentials” (February 2005): https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/plain-language/bus65-avoid-fake-degree-burns-researching-academic-credentials.pdf.

- Ibid.