One of the college graduation mementos still in my possession is a small, smooth stone upon which is inscribed “1 Samuel 7:12.” With this keepsake came a card encouraging me to keep a stone for every significant experience where I had proof of God’s providence. I kept up the tradition for a while, but keeping track of a bag of stones became increasingly difficult with each move. I did keep that first stone, however, along with a few others that marked significant events. Each stone has a story, and some even have a corresponding entry in my personal journal. In times of reflection, memory serves me well, and I remember sensory details not recorded on the pages. Other times, details evade my memory, the significance lost. These stones represent stories from the past—stories others may retell one day.

We are known by our stories—the stories we tell about ourselves, and those that are told about us. We selectively craft narratives that help us construct frameworks within which we navigate the world. From surviving a difficult experience or overcoming a personal challenge, to experiencing abject failure or personal loss, our stories have the potential to inspire, strengthen, and help someone else along his or her own journey.

When Samuel “took a stone, and set it between Mizpeh and Shen, and called the name of it Ebenezer, saying, Hitherto hath the Lord helped us” (1 Samuel 7:12, KJV), he took a ragged stone—one with jagged, rough edges. The stone represented victory obtained with God’s help and served as a visible monument, not something hidden away. The rough exterior not only offered a visual reminder of the difficult experience God’s people had just survived, but also of His intervention and leading.1 The stone’s simple purpose was to call God’s people to remember, and by doing so, to trust God completely. Samuel called the place Ebenezer (’eben ha‘ezer) which means “the stone of the help.”2 The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary puts it this way: “It is well for the Christian to go back constantly to the Ebenezers of life, where providential deliverances came to crown distrust of self, a full surrender, and trust in God.”3 The stone served as a reminder of God’s presence in times of peril in the past, assured them of God’s existence in the present, and promised God’s continued help in the future.

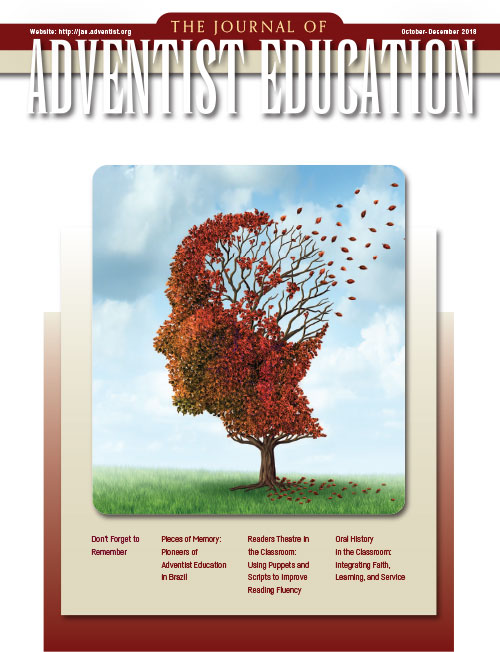

Our stories and memories of the past can give us courage to persevere. Yet, memories fade with time; and stories―by their very nature as narratives―morph and change with each retelling. Some stories are painful, with ragged, jagged chapters, and we would much rather not tell them, or we prefer to tell them in such a way that they sound more pleasant. Fivush says: “Narrating our experiences by very definition implies a process of editing and selecting, voicing some aspects of what occurred and therefore silencing other aspects.”4 The process of picking and choosing which parts to tell or not tell can lead to stories that make the teller look better, or worse, or even stories that are untrue.

Some stories are not told; some experiences are withheld in silence. And it is this silence that opens a whole new dimension of understanding and possibility. Silence could mean the story is simply not available or has yet to be uncovered. Silence increases with the passage of time—the lives of those who came before are forgotten, and those who know their stories pass into the ages themselves. Silence comes from stories that are told from one perspective—a single story without the voices of other perspectives (whether intentionally or unintentionally). Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns of “The Danger of a Single Story.” She says: “The problem with the single story is that it creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story. . . ,”5 thereby silencing all other perspectives. Textbooks and a host of other educational resources offer students one version of each story—historically, often the one told by those who hold the power to determine what should be taught.6 As educators, we must commit to presenting our students with a comprehensive picture of each topic or series of events so that their understanding will grow. This is no easy task, as it requires careful research, preparation, and a willingness to provide a more complete narrative where no voice is silenced.

Yet, ultimately, there is a single story that matters—one that every Adventist educator must proclaim with as much celebration and bravery as Samuel did so long ago: A sovereign God sent His Son Jesus to be the Savior of the world (John 3:16). Jesus came, lived, died, and rose again (1 Corinthians 15:3-5). Because of this, we have the promise of forgiveness of our sins (1 John 1:9) and the hope of Christ’s return (John 14:1-4). This story has remained unchanged for centuries and encapsulates our past, present, and future. It was taught to those who came before us; we teach it to our children; and it will continue to be taught as we await Christ’s return to this earth.7 For the Christian, the single story remains unchanged—untouched by the ravages of time or memory; and, with each retelling, blooms with the hope and promise of true, lasting assurance of God’s love for humanity.

This issue of the Journal is a collection of general articles. Several rely on the power of stories to remind us of who we are and the role we each have in making the world a better place. Dragoslava Santrac in “Don’t Forget to Remember” shares a reflection on the biblical call to remember God’s leading in history. She concludes with a call for submissions to the first online version of the Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia. Renato Gross and Ivan Gross in “Pieces of Memory: Pioneers of Adventist Education in Brazil” share three biographical sketches of pioneer Adventist educators, far removed from the present day, but whose service and dedication to growing Adventist education in South America continues through their descendants. Kris Erskine in “Oral History in the Classroom: Integrating Faith, Learning, and Service” shows teachers, kindergarten through higher education, how to bring living history into the classroom by preserving the stories of those who are still alive.

Other articles cover topics such as using Readers Theatre, puppets, and scripts to improve literacy (Tamara Dietrich Randolph); adapting Culturally Relevant Teaching to the Caribbean context (Kernita-Rose Bailey); developing effective leaders (Timothy Ellis and Megan Elmendorf); and, organizing a STEM Fest—a creative, fun, and engaging way to help students develop a love for and a desire to pursue careers in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (Ophelia Barizo).

Our hope is that this issue will provide you with an opportunity to remember and reflect upon God’s working in our past and present, so that we can all, with certainty, face the future. As the psalmist said: “I remember the days of long ago; I meditate on all your works and consider what your hands have done” (Psalm 143:5, NIV).8 Let us continue to proclaim our confidence in God as we consider His leading in our lives and the lives of our students, as well as the impact His single story will continue to have upon the world. As we reflect, may we, too, be able to say with certainty and assurance, “Hitherto hath the Lord helped us.”

Recommended citation:

Faith-Ann A. McGarrell, “Memories Etched in Stone,” The Journal of Adventist Education 80:4 (October-December 2018): 3, 46. Available at https://www.journalofadventisteducation.org/en/2018.4.1.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- F. D. Nichol, ed., The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald, 1976), 2:483.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Robyn Fivush, “Speaking Silence: The Social Construction of Silence in Autobiographical and Cultural Narratives,” Memory 18:2 (February 2010): 88. doi: 10.1080/09658210903029404.

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “The Danger of a Single Story,” TEDGlobal (July 2009): https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story/transcript?language=en.

- The adage “History is written by the victors” is often cited when discussing who determines what should and should not be taught. While this may be so, it also means that there is another side (often more than one) to a story or series of events. A fuller understanding is gained from considering what others have contributed. Quotation attributed to Winston Churchill, Brainy Quotes (2017): https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/winston_churchill_380864.

- Deuteronomy 6:4 to 7 (NIV) speaks to the importance of teaching each generation the providential ways God has worked in human history: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength. These commandments that I give you today are to be on your hearts. Impress them on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up.” Quoted from Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

- Psalm 143:5, NIV.