All institutions of learning must have and operate on a philosophy that informs teaching practice. This includes methods, content, and instructional delivery.1 For the school that intentionally aims to offer Christian education, the ideology of such an institution includes biblical principles in the teaching and learning process. The Integration of Faith and Learning (IFL) is “the raison d’etre for Christian schools.”2 Educators in Christian schools have the responsibility of presenting biblical truth while knowledge is being attained, all with the intention of transforming the heart and mind of the learners so that they reflect Christ’s character.3 This practice is “the quintessential component linking mission with content, with teacher, and with student.”4

Thus, where these interplay and linkages do not occur, IFL is unlikely to occur. “The integration of faith and learning remains the distinctive task of the Christian liberal arts college [university].”5 Furthermore, there is no reason for the existence of a Christian college campus if faith and learning are not integrated into all of the learning experiences.6 For K-12 schools, the same principles apply.

Education that fuses knowledge about God with information relevant to the acquisition of some valuable skill or preparation to enter a profession is life changing and restorative, thereby resulting in the development of “better people, citizens and employees.”7 “Wholistic education,” a term some may consider clichéd,8 remains the aim of true education. With this in mind, James Tucker questioned whether education pedagogy can address the individual’s wholistic needs (mind, body and soul) when there is no perception of a Savior.9

However, where faith is incorporated into students’ learning experiences, the aim is to cultivate men and women who have firm characters and exemplify strong values such as integrity, compassion, emotional strength, honesty, honor, humility, discipline, and moral firmness.10 Hence, the student does not simply complete a grade or course of study, but more importantly, emerges as an individual of high caliber with laudable character strengths; one who will thus be empowered to fulfill his or her duty to God as devotedly as he or she fulfills duty to humanity.

This is what the student who has completed an Adventist education (one where faith is integrated with learning) should be like.11 The Adventist philosophy of education has at its core the goal of nurturing “thinkers rather than mere reflectors of others' thoughts; to promote loving service rather than selfish ambition; to ensure maximum development of each individual's potential; and to embrace all that is true, good, and beautiful.”12

Why Assessing IFL Practice Is Important

Because of the influence of secular culture on Christian education systems worldwide, integrating faith into the learning experience is becoming an endangered practice. Further, as government/state accreditation requirements increase, colleges place demands on secondary level schools for what students will need to be college ready and to gain admission to higher education.

A biblical perspective is relevant to all aspects of education because it provides a worldview from which all other bodies of knowledge can be interpreted, and in fact provides meaning to the vast number of facts and data uncovered by science. Knowledge would in itself be irrelevant and incomplete if it did not reveal something of the One who created it all.

As a result, the teaching profession faces increased pressure based on the continuous need to meet these requirements and match industry changes. In Christian schools, this means students often do not benefit from IFL experiences because teachers are hurrying to cover the content for each course.

In addition, advances in knowledge have increased the amount of material that teachers must present and students must master to graduate (and get good scores on required tests) in order to prepare for college and a career. Although administrators may acknowledge that IFL is important, for many there have been no regular assessments that examine their level of proficiency or the extent to which it is being practiced. Further, a search for literature on factors that influence proficiency in implementing IFL, such as training, modelling, and other demographic variables, reveals a limited number of resources.13 There is a need therefore to systematically and periodically assess what is currently being done to integrate faith and learning in the classroom and to provide training where deficits have been identified. It is only through this approach that the real impact of IFL and challenges, if any, will be understood.

What the Literature Reveals About IFL and Worldview

Harry Poe’s assertion that faith, from a Christian perspective “means faith in Jesus Christ,”14 suggests that Christian education should be centered on the life and character of Jesus Christ. Thus, the root of Christian education is integrating faith into learning so that students’ worldviews can be influenced as they are encouraged to adopt a wholistic lifestyle based on biblical truths.15

However, a number of Christian colleges/universities have simply added chapel services and religious classes to the secular educational structure without embracing a Christian philosophy.16 Therefore, Christian institutions need to evaluate and align their core beliefs with Christian principles, while Christian educators must make sure that what happens in the classroom is unified, integrated, and centered on Christian philosophy.17

Douglas Phillips suggested that the attempts by some supporters of “classical Christian education” to have the writings of pagans taught to students as wisdom and “true knowledge” ought to be rejected.18 However, a theological perspective may dictate otherwise; for while the Scripture is true, not all truth and knowledge are contained or deducible from this source.19 Instead, the Scriptures present us with sufficient principles to guide our faith and conduct. Therefore, for the Christian educator, the integration of faith and learning is foundational, and the Bible should be considered “the focus of integration for all knowledge, because it provides a unifying perspective that comes from God, the source of all truth.”20

A biblical perspective is relevant to all aspects of education because it provides a worldview from which all other bodies of knowledge can be interpreted, and in fact provides meaning to the vast number of facts and data uncovered by science. Knowledge would in itself be irrelevant and incomplete if it did not reveal something of the One who created it all. 21 Christian education embraces this truth, and upon this basis, promotes the sort of education promoted by the very pillars of Adventist perspectives on education: the salvation and the restoration of God’s image in each person.22 However, according to Tucker, this position is not a global one in secular society; and, even in some Adventist communities, there is a proclivity toward secular education that is embedded in worldviews of naturalism and postmodernism in lieu of a biblical worldview. 23 However, true education, instead of merely being “the pursuit of a certain course of study,” also must include the “harmonious development of the physical, mental, and spiritual powers.”24

It is only in contemporary eras that faith is viewed as separate from education, for from the beginning of time, faith and learning have been inseparably intertwined.25 Furthermore, the creative capacity of humanity is a reflection of the creative power of God. 26 Robert Harris asserted that “the meaning of knowledge involves religious assumption.” 27 Hence, the interpretive framework of all knowledge is connected to an individual’s particular ontology (his or her theory of what exists) and epistemology (his or her theory of knowledge).

For some, there is a lack of understanding of the importance of integrating faith and learning in Adventist education, and perhaps, too, what IFL really is and what such an integration involves or looks like. Foremost in the literature is a clarification of what integration entails and how the two concepts, “faith” and “learning,” are combined in a new way. Dawn Morton conceived of integration as the process whereby faith and learning are combined so that “both need to be understood as complimentary. They are not in competition with each other but working side by side.”28 The error of a disjointed approach to faith and learning is manifested in schools where religious education courses are distinct from the rest of the curriculum and are approached as simply another subject to be learned rather than a way of life to be applied and exemplified within each student.29

Shawna Vyhmeister’s work explains the complexity of integrating faith and learning in school curricula by describing the numerous challenges to be faced, such as the rampant secularism and sinfulness of the world itself; the superficiality of some educators in their attempt to engage in faith-based instruction; and the perception of young persons that the church is judgmental and critical rather than warm and accepting.30

In order for IFL to be properly assimilated into the formal curriculum, the process must begin with the teachers―who should be Adventists since Adventist education cannot exist without Adventist teachers.31 George Knight explained that just as a Christian teacher is armed with the right tools to execute Christian education, so too, is the Adventist teacher armed with what is necessary to deliver Adventist education and its most important objective: leading students into a personal saving relationship with Jesus.32 These teachers should view their subjects as a part of the pattern of God’s truth.33 There is also the need for teachers to demonstrate a Christlike character in their unconditional support and regard for students.34

Research on IFL Integration at an Adventist University in the Caribbean

A study conducted October 2014-March 2015 at an Adventist university in the Caribbean sought to examine and ascertain the faculty members’ proficiency in implementing IFL.

A quantitative approach with a cross-sectional survey design was used. Data were collected once for this study using a two-part questionnaire. From a faculty complement of 250, convenience sampling was used, and 100 members of faculty were surveyed. Section A of the instrument contained demographic questions, while Section B contained the Integration of Faith and Learning Survey (IFLS). The demographic survey consisted of six questions concerned with the respondents’ gender, religious affiliation, years of service in a Christian school, attending a Christian school while growing up, the discipline in which they were teaching, and training in IFL. The questionnaire used in this study was a modification of Eckel35 done by Peterson.36

The IFLS had 28 items, all of which were measured on a five-point Likert scale. Faculty proficiency in the integration of faith and learning was measured based on four subscales: Level, Equipped, Ability to Do, and Intentionality. Each scale measured very different things. For example, the Level subscale of the integration of faith and learning measured a teacher’s general knowledge and preparedness to practice IFL in the classroom; the Equipped subscale measured a teacher’s instructional skills and approaches as well as resources to practice IFL, while the Ability to Do subscale measured a teacher’s capacity to practice IFL based on both external and internal factors. Lastly, the Intentionality subscale measured the teacher’s conscious or purposeful implementation and wilful desire or intent to improve in his or her classroom integration of faith and learning. This scale also measured the teacher’s coordination with other instructors to amplify or maximize the impact of the integration of faith and learning on students in the classroom.37

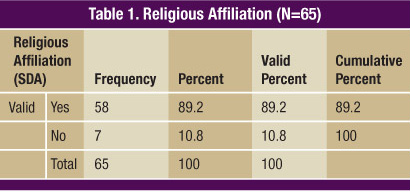

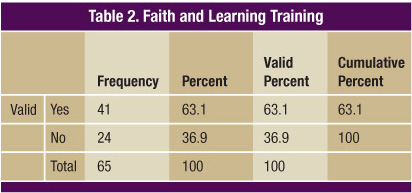

The researcher examined the level of faith and learning integration between the colleges and schools of the university. This sample included 65 respondents, representing all the colleges of the faith-based institution. More than half (58.89 percent) of the respondents were practicing Seventh-day Adventist Christians (see Table 1). Interestingly, 50.77 percent of the informants had not attended a Christian school growing up. The largest subgroup of the faculty surveyed (29 percent) were from the business college, with the college of social sciences accounting for 23 percent, and another 19 percent from the college of education and leadership. The majority of the faculty surveyed (63 percent) stated that they had received some form of training in the integration of faith and learning (see Table 2).

The research questions for the study assessed and compared the level of faith and learning integration occurring among faculties in the academic disciplines at the university.38 The researcher divided the research questions and created a summary of the findings for each of the two questions. The research questions were as follows: (1) What is the level of proficiency among faculty at the university in the integration of faith and learning? (2) To what extent is there a difference in proficiency in IFL based on: (a) academic discipline (b) training in IFL?

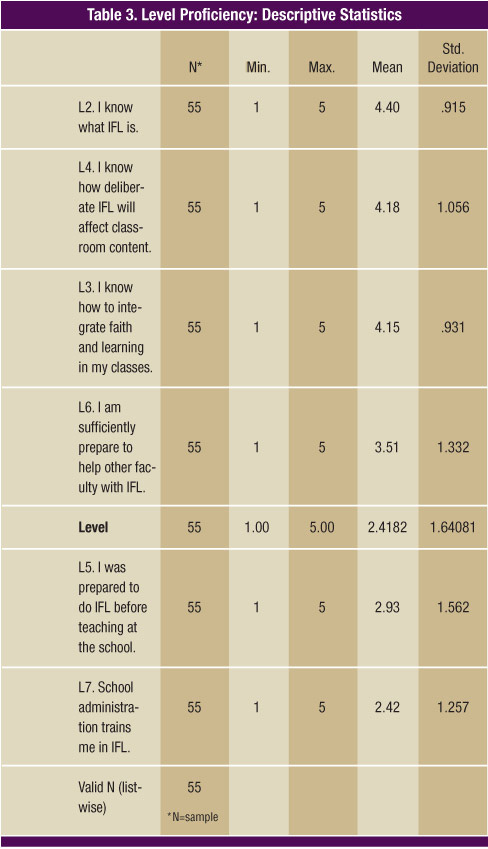

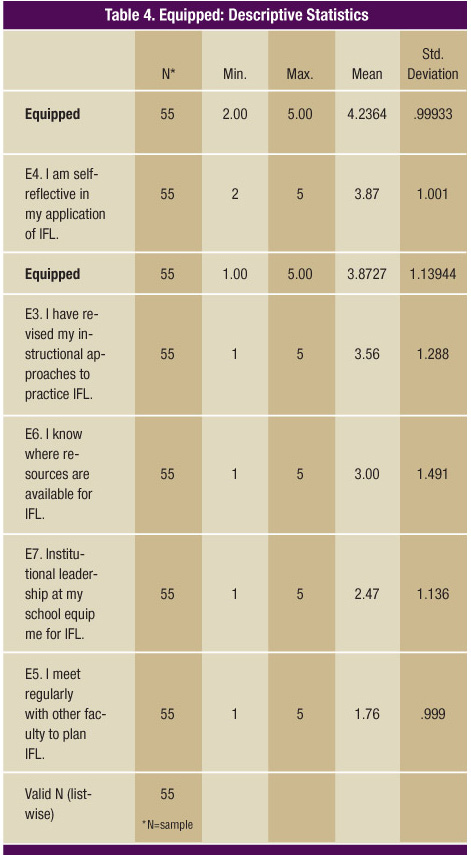

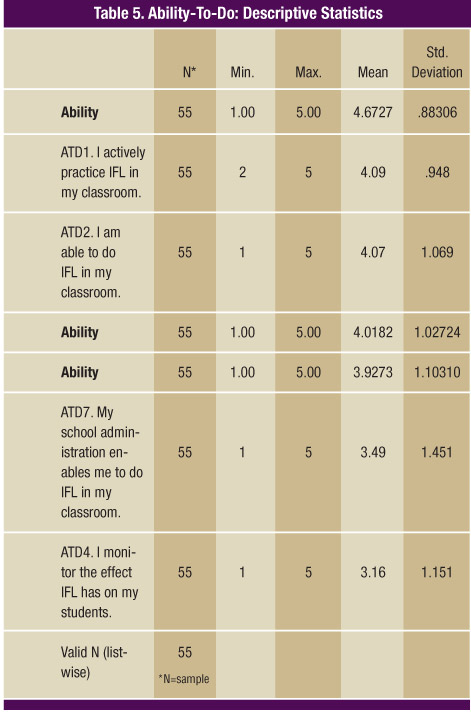

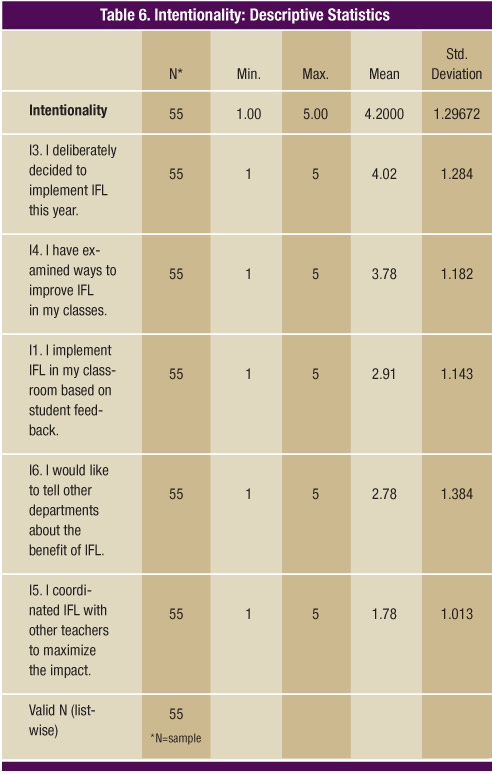

The study could not delineate among the colleges the level of competencies relating to the four areas (Level, Equipped, Ability to Do, and Intentionality) based on the assessment of the results generated from the one-way ANOVA. Hence, there was no need to do the post hoc test, which would only show where the differences lay. However, further analysis through descriptors and central tendency statistics of descending order of mean on each of the competencies showed that there were some weak areas within each of the four levels (see Tables 3-6).

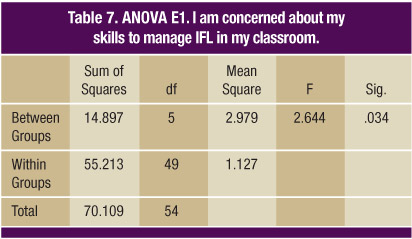

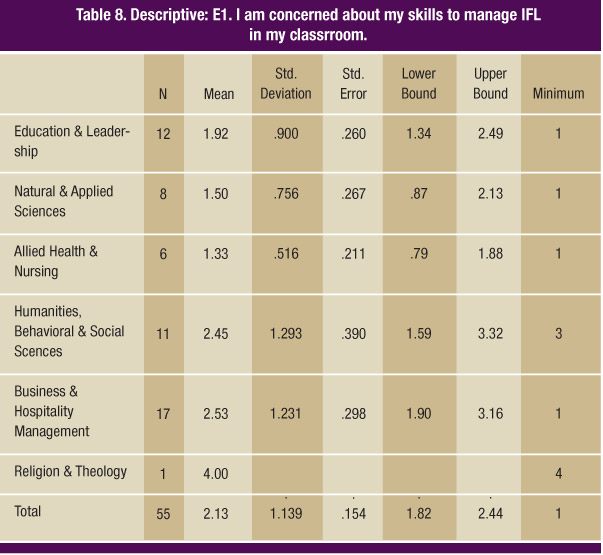

The data showed that faculty had a fair knowledge of IFL and knew how deliberate IFL would affect classroom content (see Table 3). The weaknesses that appeared in Equipped showed that faculty did not meet regularly with their peers to plan IFL, institutional leaders didn’t equip faculty for IFL, and faculty did not know where to obtain resources for IFL (see Table 4).The data showed that faculty possessed the ability to do IFL and had the necessary authority to implement IFL in the classroom (see Table 5). The data dealing with the competence of intentionality revealed that members did not coordinate with their peers to maximize the impact of IFL. Notably, they did not share with other colleges within the institution the benefit of IFL since no framework existed to do so; furthermore, they did not seek or receive feedback from students on IFL in the classroom. Conversely, the data revealed that faculty were making efforts to implement IFL (see Table 6). Further assessment of question one under the equipped competence showed that there was a statistically significant difference among the colleges. This meant that some faculty did not possess the skills necessary to effectively manage IFL in the classroom. A large “F” statistical value was evidence against the null hypothesis, since it indicated more differences between groups than within groups (see Table 7). The colleges of nursing, natural and applied sciences, and education and leadership at the institution surveyed had the greatest deficit in the skills teachers needed to effectively manage IFL in the classroom (see Table 8).

Discussion of Findings

While the findings from the study may not be unique to the specific institution investigated, the findings may not be generalizable because only one institution with unique Caribbean cultural and social factors was studied, and convenience sampling may not necessarily allow for adequate representativeness of the population. Given that this study has employed the use of that sampling technique, the findings should therefore be generalized only with caution, as the willing participants may not adequately represent the population. One of the greatest challenges of self-reporting is credibility due to the tendency of respondents to exaggerate or understate the description of their own actions. Also, faculty members, due to time constraints, may be tempted to randomly respond to items without attending to the content.39

Addressing the level of proficiency among faculty in the various colleges, the data revealed that faculty were not prepared to teach in an integrated manner before coming to the university and that the university administration had not provided training for faculty in how to integrate faith and learning. Conversely, the data showed that faculty had a fair knowledge of IFL and knew how deliberate IFL would affect classroom content.

Further findings revealed that there were weaknesses that appeared in the Equipped competency because faculty didn’t meet with other faculty to plan IFL, institutional leaders didn’t equip faculty for IFL, and faculty did not know where IFL resources. Notably, further assessment of question one under the Equipped competence showed that there were statistically significant differences among the colleges, which means that some of the faculty did not possess the skills necessary to effectively integrate faith and learning in the classroom.

Further analysis of the question using descriptive statistics revealed that faculty in the colleges of allied health and nursing, natural and applied sciences, and education and leadership showed the greatest deficit in skills needed to effectively manage IFL in the classroom. However, the data show that all those surveyed possessed the Ability to do IFL and had the necessary authority to implement IFL in the classroom. Moreover, the data dealing with the competence of Intentionality revealed that faculty didn’t coordinate with their peers to maximize the impact of IFL. Notably, faculty did not share with other colleges and schools the benefit of IFL since no framework to do so existed, and further, they did not seek or receive feedback from students on IFL in the classroom. Conversely, the data revealed that all of the ones surveyed were making an effort to implement IFL.

General Recommendations

Institutional leaders need to be intentional and deliberate in ensuring that training is provided to equip faculty with the skills necessary to effectively implement IFL in the classroom. The author further recommends that a faith-and-learning committee be established at the institutional and union levels with the responsibility to execute the following:

- Create a conceptual framework/model to implement the integration of faith and learning beginning with Adventist primary schools so that when students reach university level, they will have had the foundation laid;

- Implement a developmental process and competency scale to measure faculty knowledge, skills, and dispositions for faith integration monitored within the Faith Integration and Faculty Evaluation System: and

- Incorporate faith integration in the curriculum, and provide clear learning outcomes for faculty to include in course planning.

Mentoring

As far as equipping faculty with the resources and skills needed to successfully practice IFL is concerned, a mentorship program in which more competent IFL-practicing faculty members are paired with those needing support may be useful. Such a mentorship program could be further enhanced by quarterly workshops on IFL as well as formal continuing-education courses and units specially designed to target the four subscales. Faculty members may be more inclined to integrate faith and learning if they feel more supported and believe that administrators have a keen interest in their instructional proficiency and development. Educational administrators should therefore ensure that there is budgetary allocation for IFL resources for faculty members; and where necessary, additional funding is obtained through fundraising activities and other types of sponsorship.

Collaboration

Given the need for collaboration and coordination in IFL, it would be prudent to develop a system of inter- and intra-departmental sharing of best practices in integrating faith and learning at higher education levels. At the K-12 level, this system may also take the form of bimonthly meetings to review lesson plans and instructional delivery approaches/strategies and may incorporate the use of technology such as video-recorded sessions for critique and feedback. Additionally, an IFL newsletter outlining tips, emerging trends, news, and updates may be published for the benefit of all administration and faculty.

Evaluation and Assessment

The impact of systems, programs, or procedures is best measured by appropriate assessment mechanisms. Against this background and within the context of the findings of the study, a detailed monitoring and evaluation instrument should be developed by administrators to assess, among other things, the extent to which the integration of faith and learning takes place; the impact of IFL on students as well as faculty, the areas where improvement is needed, based on identified gaps in the knowledge; and the competence of all faculty to perform self-assessments.

This study should be extended to include a larger population of faculty, administrators, staff, and students. Further, it could include the use of projective techniques (direct and indirect ways of identifying motives and intentions), observation, and direct qualitative techniques of focus groups combined with in-depth interviews.

Conclusion

With these thoughts in mind, college and university academic administrators must look for ways to provide opportunities for faculty to learn how to effectively integrate faith with learning. Orientation seminars, professional-development training sessions, small-group collaboration, or even a teaching-and-learning center on campus that provides resources and assistance as faculty develop their competency, are all ways this could be done. A trained teaching faculty will be able to create classrooms that integrate faith with learning in meaningful ways to the benefit of students.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended citation:

Michael H. Harvey, “The Importance of Training Faculty to Integrate Faith With Learning,” Journal of Adventist Education 81:3 (July–September, 2019): 9-16. Available at https://www.journalofadventisteducation.org/en/2019.81.3.3.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- Jeff Astley, Leslie Francis, and Andrew Walker, eds., The Idea of a Christian University: Essays on Theology and Higher Education (Waynesboro, Ga.: Paternoster Press, 2004).

- Constance C. Nwosu, “Integration of Faith and Learning in Christian Higher Education: Professional Development of Teachers and Classroom Implementation.” PhD diss., Andrews University, 1999, 3.

- Robert Littlejohn and Charles T. Evans, Wisdom and Eloquence: A Christian Paradigm for Classical Learning (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway Books, 2006).

- Mark Eckel, The Whole Truth: Classroom Strategies for Biblical Integration (Longwood, Fla.: Xulon Press, 2009), 136.

- Arthur F. Holmes, The Idea of a Christian College (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1987), 8.

- Robert T. Sandin, The Search for Excellence: The Christian College in an Age of Educational Competition (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1982).

- Dawn Morton, “Embracing Faith-Learning Integration in Christian Higher Education,” Ashland Theological Journal 360 (2004): 65: http://www.biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/ashland_theological_journal/36-1_063.pdf.

- James A. Tucker, “Pedagogical Application of the Seventh-day Adventist Philosophy of Education,” Journal of Research on Christian Education 10: Special edition (Summer 2001): 173, 174.

- Ibid.

- Wilfrida A. Itolondo, “The Role and Status of Christian Religious Education in the School Curriculum in Kenya,” Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies 3:5 (October 2012): 721-729: https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-3089447831/the-role-and-status-of-christian-religious-education.

- Charles Scriven, “The Ideal Adventist College Graduate” (2008):http://circle.adventist.org/files/download/IdealGraduate.pdf.

- Humberto Rasi et al., “A Statement of Seventh-day Adventist Educational Philosophy Version 7.8,” Journal of Research on Christian Education 10: Special edition (Summer 2001): 347-355: https://education.adventist.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/A_Statement_of_Seventh-day_Adventist_Educational_Philosophy_2001.pdf.

- This lack of resources is specifically unique to the Caribbean context.

- Harry L. Poe, Christianity in the Academy: Teaching at the Intersection of Faith and Learning (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2004).

- Daniel C. Peterson, “A Comparative Analysis of the Integration of Faith and Learning Between ACSI and ACCS Accredited Schools.” PhD diss., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2012.

- Harold H. Ditmanson et al., Christian Faith and the Liberal Arts (Minneapolis, Minn.: Augsburg, 1960). Quoted in George R. Knight, Philosophy and Education: An Introduction in Christian Perspective, 4th edition (Berrien Spring, Mich.: Andrews University Press, 2006), 164.

- Knight, Philosophy and Education: An Introduction in Christian Perspective, ibid., 164.

- Douglas M. Phillips, introduction to The Bible Lessons of John Quincy Adams for His Son by John Q. Adams (San Antonio, Texas: Vision Forum, 2000).

- Holmes, The Idea of a Christian College.

- Knight, Philosophy and Education: An Introduction in Christian Perspective, 213.

- Robert A. Harris, The Integration of Faith and Learning: A Worldview Approach (Eugene, Ore.: Cascade Books, 2004).

- Ibid.

- Tucker, “Pedagogical Application of the Seventh-day Adventist Philosophy of Education,” 169-185.

- Ellen G. White, Education (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1903), 13.

- Tucker, “Pedagogical Application of the Seventh-day Adventist Philosophy of Education.”

- Ibid.

- Harris, The Integration of Faith and Learning, 2.

- Morton, “Embracing Faith-Learning Integration in Christian Higher Education.”

- Itolondo, “The Role and Status of Christian Religious Education in the School Curriculum in Kenya,” 722-723.

- Shawna Vyhmeister, “Building Resilient Christians: A Goal of Adventist Education,” Journal of Adventist Education 69:2 (December 2006/January 2007): 10-18: http://circle.adventist.org/files/jae/en/jae200669021009.pdf.

- George R. Knight, Educating for Eternity: A Seventh-day Adventist Philosophy of Education (Berrien Springs, Mich.: Andrews University Press, 2016), 78.

- Frank E. Gaebelein is quoted as saying there would be “no Christian education without Christian teachers” (see Frank E. Gaebelein, The Pattern of God’s Truth: Problems of Integration in Christian Education (Chicago: Moody, 1968), 35. George Knight extends this sentiment by stating “there can be no Adventist education without Adventist teachers” (see Educating for Eternity: A Seventh-day Adventist Philosophy of Education, 78).

- Frank Gaebelein, Christian Education in a Democracy. Quoted in Daniel C. Peterson, “A Comparative Analysis of the Integration of Faith and Learning Between ACSI and ACCS Accredited Schools.” PhD diss., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2012.

- Vyhmeister, “Building Resilient Christians: A Goal of Adventist Education.”

- Mark David Eckel, “A Comparison of Faith-learning Integration Between Graduates from Christian and Secular Universities in the Christian School Classroom.” PhD diss., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2009.

- Daniel Carl Peterson, “A Comparative Analysis of the Integration of Faith and Learning Between ACSI and ACCS Accredited Schools.” A PhD diss., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2012.

- The data were analysed using the SPSS Version 22.

- After the data were compiled and transferred into SPSS, the numerical scoring scale was adjusted from high to low for the negatively worded questions in the instrument (L1R, E1R, E2R, ATD3R, ATD5R, ATD6R, I2R, and item 7 was deleted from the intentionality scale). A reliability test was done on each of the subscales, and each was found to be suitable for use in the study. The data were analyzed using the two research questions guiding this study.

- John W. Creswell, Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research (Boston: Pearson, 2012).