Educators in Adventist schools face challenges posed by the influences of secularism in public education when they choose a textbook, look for a video to illustrate a point, and even when they select articles for students to read. The difficulty often comes from the non-alignment of faith with the widely accepted theories of a discipline, leading to the question: “How do I position my Christian faith when seeking to understand the tenets of the discipline?”

Christian educators are distinguishable from non-Christian educators in several ways. Christian educators believe the Bible is the Word of God, and they accept as Truth that Jesus is the earthly manifestation of God the Creator and the anointed Son of God. Christians engage with the Bible for understanding, for devotion, and for spiritual growth. They believe Jesus Christ came to earth to save sinners and accept the Truth of the Bible as their guide for thinking and living.

The process of thinking about the Bible can take many forms, such as simple questioning, forming useful self-regulatory judgments,1 reflective skepticism,2 and moving thinking beyond human limitations by seeking God’s understanding and wisdom.3 Educators are constantly seeking understanding to address issues within their discipline, and Christian educators seek to reconcile their faith in biblical truths with the areas of their disciplines that are influenced by secular thought. In this article, I will discuss the developing critical-thinking movement and the implications of the secular approach for religious faith and practice.

Background and Secular Goals of Education

Over the past several decades, many educational movements have affected education practice and policy. And, as theories become practice, these movements continue to have an impact on Christian educators as they seek to align biblical principles with subject content and with learning issues such as the need to improve students’ thinking and problem-solving skills and motivation, and the impact of students’ low self-esteem on their ability to learn.

One primary example is the self-esteem movement, which can be traced back to 1969 and the seminal book by Nathaniel Branden, The Psychology of Self-Esteem. In this work, Branden asserted that the key to success in life is to develop children’s positive self-esteem. With the publication of his thoughts, the task of parenting and education morphed into the mission of building confidence in subsequent generations of students. One way to increase this confidence was to teach children to think critically about the world around them.

Later, the 1980s gave rise to new expressions of the self-esteem and critical-thinking movements through incorporating them into the school curricula. Since the early ’80s, I have been pondering what these teachings would mean for shaping a generation that would mature in the 21st century.

Well, now—two decades into the 21st century—critical thinking and self-esteem have converged into a generational expression of the self that is often dismissive of the influence of external authorities. The haste to embrace self-expression and the rejection of limitations on self-expression or opinions seem embedded in the authority of self-knowledge. This rush to speak “my truth” or “my opinion” suggests that the individual believes he or she possesses full and comprehensive knowledge.

The story of the blind men and the elephant is a familiar one. Many traditions also tell the story of the ant who from the underbelly of an elephant looks up and declares there is no sky because the dark hair of the elephant is all that it can see. Perspective is limited in any context.

Whether a limitation is created by the natural limits of individual understanding, lack of awareness, or by contextual constraints on vision, any limitation challenges one’s views, including how Christians think about Scripture and life. It is difficult for the person who overvalues self-expression to engage in meaningful dialog with the person who seeks to engage in thoughtful reflection from different points of view.

A relativistic approach to truth is often joined by another common concept that many think to be new: the concept of “open-mindedness.” For many, a feature of the intelligent mind is the ability to be open-minded, to be available mentally for new discoveries and new ideas. They believe that truth is ever evolving; thus, a closed mind is self-limiting, while an open mind is progressive and ever learning.

Open-mindedness is not a new 21st century concept. It is common within education and particularly so in higher education. According to leading thinkers like John Dewey and Bertrand Russell,4 open-mindedness is one of the fundamental aims of education and approaches to critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Learning

Critical thinking has many definitions, ranging from the ability to engage in useful, self-regulatory judgment5 to the broad ability to interpret information and approach problems correctly,6 or to the simple ability to analyze arguments.7 Educators have called for the teaching of critical-thinking skills; yet results from implementation of critical thinking into the curriculum have not shown conclusively that the small gains in critical thinking were not simply the effect of learning in general, and have not shown that these gains resulted from the specific teaching of critical thinking.8 Regardless of definitions and the reported increases in critical-thinking skills,9 the critical-thinking movement has now replaced the self-esteem movement that swept across schools in America at all levels during the 80s and 90s.10

Educators and employers consider critical thinking (i.e., thinking, analysis, and problem solving) to be an essential life and workplace skill. This interest in critical thinking is evident in the number of universities,11 including Oakwood University (OU) in Huntsville, Alabama, U.S.A, where I serve, that give focused attention to achieving specific learning outcomes in critical thinking. This is demonstrated through writing12 and employers’ desire for employees who are competent in these skills for analysis and problem solving.13

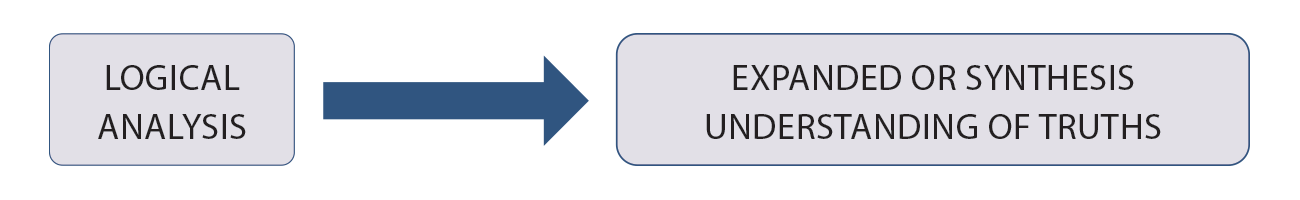

Approaches to teaching and evaluating critical thinking skills vary. When teaching critical thinking, some instructors guide the process of thinking about one’s thinking with goals varying from fair-mindedness to evaluation. Others take a more discipline-focused approach14 and guide thinking within a discipline or profession, such as scientific reasoning within the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) disciplines. Thinking about one’s thinking is a critical need both to become educated and to be a highly productive employee and an informed citizen. Society’s need for individuals to possess thinking and problem-solving skills is on the increase. However, when it comes to the frameworks of the critical-thinking movement, secular and often anti-religious teachers are pervasive in schools and universities worldwide (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Critical Thinking and Faith

Critical thinking is often presented as being in tension with religious faith or any way of thinking that allows for acceptance of the Bible as Truth. At first glance, the terms “critical thinking” and “religious faith” seem quite disparate―especially to the secular mind. Christians see a relatedness, with the Bible being the source of Truth with which the mind engages to understand the world—and believe that meaning originates from Scripture. With Scripture as the foundation for living, human contributions to thought are to be considered secondary to the principles derived from Scripture. Scripture begins with the beginning of everything and ends with God’s ultimate plan for this life and life everlasting. And in between is found guidance for the Christian’s journey. The Bible addresses the same questions as human philosophy: from the origin to the end of life, and how we should think and behave in between.

How Adventist schools should integrate the Bible with life and living, and teach students to do the same, is what we are addressing in this article. This philosophical orientation originates from Scripture (see Figure 2) and forms the worldview of the Christian. It is a worldview that says faith is one of the absolutes for living as a Christian, and that faith in the unseen can and does coexist with reason.

Figure 2.

Taken from Henry A. Virkler, Henry A. (1993, 2006). A Christian’s Guide to Critical Thinking (Nashville: Thoman Nelson, Inc., 2006).

Open-mindedness is an element of thought that has reappeared in the 21st century and seems most appealing to millennials.15 Like all other ways of thought, open-mindedness is a practice that should be critiqued. Most individuals can agree that before an opinion is formed, study must be given to the various contributions to the idea. The form of open-mindedness that exists today is one that says rationalism and scientific ways of knowing are superior to belief in the supernatural, and dismisses the Christian Bible as a source of Truth. In fact, the mind is currently conditioned in some educational strategies to accept only evidence-based knowledge and to remain constantly open to novel ideas, ever remaining in the seeker mode.

Among the many leaders of the critical-thinking movement, The Foundation for Critical Thinking is well known for its rejectionist position toward religion. This foundation sees religion as antagonistic toward critical thinking—viewing biblical teachings as dogma and a limitation or barrier to critical thinking. However, Christians who view the Bible as the Truth, the Word of God, are counseled to also practice open-mindedness; an open-mindedness that is open to and guided by divine revelation. In Messages to Young People, Ellen White urges that in the “study of the word, lay at the door of investigation your preconceived opinions and your hereditary and cultivated ideas. You will never reach the truth if you study the Scriptures to vindicate your own ideas. Leave these at the door, and with a contrite heart go in to hear what the Lord has to say to you. As the humble seeker for truth sits at Christ’s feet, and learns of Him, the word gives him understanding. To those who are too wise in their own conceit to study the Bible, Christ says, you must become meek and lowly in heart if you desire to become wise unto salvation.”16 And while this statement primarily addresses misinterpretation of the Scriptures, it is applicable to the level of open-mindedness required of critical thinkers. This approach suggests open-mindedness as a type of intellectual humility necessary to persist and find new solutions to persistent problems such as vaccine development for novel viral infections (such as COVID-19), or other diseases such as cancer or the “common” cold.

Christians are encouraged to conform themselves to the authority of the Word: “Do not read the word in the light of former opinions; but, with a mind free from prejudice, search it carefully and prayerfully. If, as you read, conviction comes, and you see that your cherished opinions are not in harmony with the word, do not try to make the word fit these opinions. Make your opinions fit the word. Do not allow what you have believed or practiced in the past to control your understanding. Open the eyes of your mind to behold wondrous things out of the law. Find out what is written, and then plant your feet on the eternal Rock.”17 And from that posture, move to understanding the problems being addressed, allowing the foundation of Scripture to guide your thinking about thinking.

Closure is encouraged, a closure that comes from confidence in the Word as Truth when Scripture speaks to the matter. Christians are called to be mindful, to be thinkers always—to be thinkers and not mere reflectors of the thoughts of others.18 This calling means that Christians, and especially Christian educators, must take care to mindfully engage with what occupies the eyes, ears, and mind. The senses are always engaged—and sometimes assaulted—often without people having decided to screen out or to bring into their psyche the things they desire to influence who they are and will become.

Additionally, when addressing a problem, it is useful to the process of discovery to recognize that closure may be premature. Whether in the laboratory or the field, open-mindedness allows the researcher to remain in a learning posture, even when a method or triangulation of methods suggests security in the finding.

I posit that critical thinking is desirable for the Christian, now more than ever before. And the call for open-mindedness is not just an intellectual calling, but the believer’s calling. However, for the Christian intellectual, open-mindedness is to be subjected to critical analysis so that it can rest on foundational truths of the Bible and be overshadowed by the Bible’s call for obedience, love, justice, and mercy. The mind of the Christian is never left to its open-ended journeys; The Bible calls all Christian to think and become. Let me explain.

Scholars are, by nature, integrationists, and Christian scholars are no different. They are first believers in the truth—the essence—of the Bible. With the Bible as their foundation, and the orientation of a believer, scholars examine the world around them from the perspective of the Bible. They question even the innocuous, simplistic, and maybe even the simple things in their world. The Christian scholar sees current-day events and asks, “What meaning does my biblically based faith bring to this issue so that I can better understand how God wants me to think and to respond?”

Biblical Foundations for Learning

It is when “Truth” is foundational for “truth” that the foundations of faith are integrated with life. While thinking about thinking (critical thinking), Adventist educators must understand that it is not just the elements of thought that are encouraged but also the philosophical orientation toward thought and behavior. Humanism, rationalism, the scientific method, and their inherent approaches to the construction of knowledge are some of the dominant philosophies that as far back as the 20th century have had an impact on thought and action, especially in the West. The process of education, knowing, and being have foundational principles and approaches to critical thinking.

For example, The Foundation for Critical Thinking19 opposes the Bible as the foundation for one’s thinking. And although the elements of thought espoused by Richard Paul and Linda Elder, founding fellows at The Foundation for Critical Thinking, can help the thinker to deepen and widen his or her perspective, it is the rejection of the Bible as Truth that is problematic and renders the overall model as inappropriate for developing the mind and heart of the Christian. Life has its source in God, and the Bible is the revealed Word of God. The Word is Truth and records God’s purpose of redemption, salvation, and restoration. The Christian20 is no mere reflector of others’ thoughts; the Christian should think higher than the highest thought can reach.21 And that higher thoughtfulness is, in fact, God’s ideal for His people: “Godliness—godlikeness—is the goal to be reached.”22

Parents are to be the first teachers of their children, developing mental rigor by cultivating the “moral and intellectual powers.”23 Yet the school rather than the parent has become the dominant shaper of character with its intentional approach to teaching secular approaches to critical thinking. Therefore, we ought to pay attention to what Adventist schools teach as truth and the possible impact of the teachings on the student’s faith in the Word of God.

Teaching, Learning, and Faith

Recent studies24 reveal that when students who espouse religious faith enter college, while they may lose faith, they ultimately regain some faith if they remain connected to their community of faith while attending a secular college. Students who enter without faith do not gain faith while studying in a secular environment. Certainly, we applaud the first group for regaining some faith. Most concerning is the fact that for a significant period, while in a secular college, they lose their personal faith. And upon graduation they have not increased their faith, some have only regained some faith, and others have lost all faith. The maturation of faith many students experience during late adolescence—the formative years for the adult—can be lost in college. This sad outcome is the result of the secularization of knowledge, a focus on the scientific method as the foundation for truth, and a prevailing anti-God and anti-Bible bias in much secular education.

The purpose of questioning is to drive further inquiry, not to stop discovery; questioning aids discovery. The Christian critical thinker seeks to know: “‘Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened for you’” (Matthew 7:7, NIV).25 The desire to know, undergirded by deep study, prayer, and reflection will lead the Christian scholar to a deeper relationship with Christ. “We are called to restore Christ-centered education.”26 That restoration will first lead students into a relationship with Jesus Christ; and, second, effectively input a distinctively Seventh-day Adventist worldview designed to provide the biblical foundations for moral and ethical decision-making.27

An Illustration From Oakwood University

The entire spectrum of Seventh-day Adventist schools—preschool through graduate level—has a stewardship opportunity. Joining forces with the church and home, the school can intentionally offer a biblically grounded education that graduates individuals with strong faith. Leslie Pollard, president of Oakwood University, is known for commenting from time to time that Adventist education prepares students “not just for four years but for 40 years and finally forever.” Yes, the years of matriculation and career preparation are important, but most important are the years where students apply the transformative education received while on Adventist college and university campuses: the years post-college and leading into eternity.

After all, the purpose of education and redemption are one: to save lost souls. The clarion call is for a biblical approach to critical thinking. And a caution is due. The assumption cannot be made that simply being an Adventist school is a guarantee that faith is being developed. A series of questions can help stimulate thinking about faith development. For example:

Is the mission of the school explicitly Seventh-day Adventist and biblical in its desired outcomes?

Is the goal of the school and its curriculum to disciple, to transform students, and to strengthen faith in the Adventist message?

How does the school report to parents, students, and constituents on its achievement of mission and goal achievement?

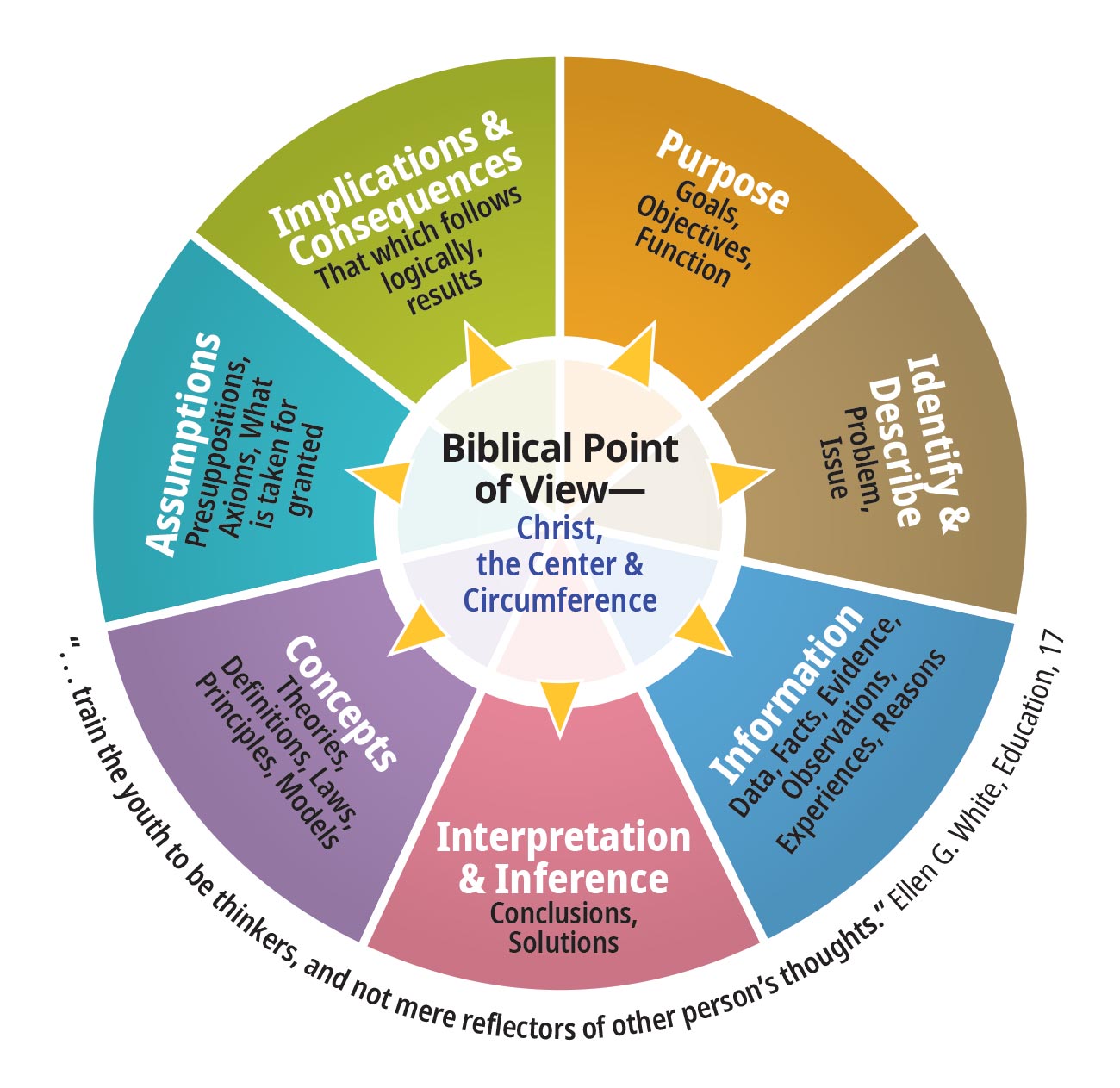

It is with this missional focus that Oakwood University studied secular models28 and developed what the university administration, faculty, and staff believe is a comprehensive biblical model (see Figure 3) for critical thinking, analyzing, and problem solving (TAPS: Thinking Analyzing Problem Solving). This model’s foundation is centered in the Word of God, supporting logic is grounded in the Word, and the process of arriving at an expanded understanding and synthesis is also grounded in biblical truth.

Figure 3. Model for Thinking, Analyzing and Problem-solving (TAPS)

NOTE: Key tenets of the biblical worldview are first, the biblical metaphysics/assumptions inform view of the universe and God’s relationship to it (Genesis 1:1); second, the affirmation of revelation informing reason (e.g., Psalm 19); third, assumption of God’s presence in and through the world (e.g., Colossians 1); and, finally, Christ as the center and circumference of belief structures (e.g., Colossians 1). All analytical thinking (TAPS Model) is informed by these key assumptions.

During the university’s annual Faculty Development Summer Institute on “Biblical Foundations in the Disciplines,” lead faculty are trained to examine the philosophical foundations for the respective disciplines in which they teach, research, and serve. Faculty are invited by institute facilitators to compare the biblical worldview and its presuppositions, assumptions, and teachings with the secular foundations upon which their disciplines often rest. This process of biblical deconstruction of the knowledge undergirding the disciplines and the accompanying reconstruction is liberating for faculty.

Using the TAPS Model, faculty are helped to integrate their secularized careers and spiritual lives. Faculty return to their academic departments and work with the dean to train their faculty-peers on how to think biblically about the disciplines housed in their departments. This is done in the context of the Seventh-day Adventist faith. With the biblical foundation established, faculty learn how to communicate the integration of their faith with the academic discipline through modeling and instruction (see Box 1).

Oakwood University’s critical-thinking model originates from the belief and understanding that truth must be grounded in the Truth, both written and incarnate. The model is Christ-centered and based on the principle that “In the highest sense the work of education and the work of redemption are one, for in education, as in redemption, ‘other foundation can no man lay than that is laid, which is Jesus Christ.’”29 Jesus Christ was and is made flesh and was and is the ultimate revelation of God—which points to God as Creator, Savior, and Lord. In Our High Calling, Ellen White wrote: “Christ, His character and work, is the center and circumference of all truth. [And because] He is the chain upon which the jewels of doctrine are linked. In Him is found the complete system of truth.”30

Oakwood University’s model (Figure 3) presents Christ as the center and circumference of the thinking process.31 During faculty orientation, President Pollard provides a theological orientation and states that Adventist educators are to respond to Ellen White’s century-old challenge in a one-question test to higher education, “Is [higher education] fitting us to keep our minds fixed upon the mark of the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus?”32

Conclusion

Individual perspective is limited in any context. How Christian educators think about Scripture and life is limited without the guidance of the Holy Spirit into all truth.33 The Christian approach is to first ask, “What does the Word say about this?” and then to thoughtfully reflect from different points of view with intellectual submission to God’s Truth. This thoughtful reflection should be paired with deep study, and prayerful discussions and consultations with peers and colleagues. If higher education does not begin and end with a “God First” foundation, then it is incapable of strengthening faith in God. Adventist schools are to maintain God at the center and the circumference of thinking and produce graduates who not only remain faithful believers, but also become believers, as well. Seventh-day Adventist educators at all levels of education must encourage adults interested in enrolling to question the missional focus of the school and its curriculum before registering in a course of study because there are truths that are eternal.

Every learning experience should engage students in the process of integration, discovering new knowledge and comparing new knowledge claims to already accepted knowledge, attempting to fit the two together into a consistent and coherent whole. Consistency and coherence are the keys to faith integration. The biblical and historical foundations must be established before concepts can be brought together with coherence. This requires conceptual reorganization but ensures that Bible is foundational to learning—and thus should be implemented at all levels of Seventh-day Adventist education.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended citation:

Prudence LaBeach Pollard, “Critical Thinking, the Bible, and the Christian,” The Journal of Adventist Education 83:4 (October-December 2020): 17-23.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- Abrams and others note that identity-building behaviors are developed through self-regulatory judgments. See Dominic Abrams and Michael A. Hogg, “Group Processes and Intergroup Relations Ten Years On: Development, Impact and Future Directions,” Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 11:4 (October 2008): 419-425; and Adam Rutland and Dominic Abrams, “The Development of Subjective Group Dynamics.” In Sheri R. Levy and Melanie Killen, eds., Intergroup Attitudes and Relations in Childhood Through Adulthood (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2008), 47-65.

- John E. McPeck, Critical Thinking and Education (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981), 7.

- Ellen G. White, Education (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1903), 18.

- Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian and Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1957).

- Abrams, Hogg, and Rutland define critical thinking as the ability to engage in useful, self-regulatory judgment.

- Both McMillan (1987) and Ernest Pascarella (1989) present critical thinking as the ability to interpret information and approach problems correctly. See James H. McMillan, “Enhancing College Students' Critical Thinking: A Review of Studies,” Research in Higher Education 26:1 (1987): 3-29; and Ernest T. Pascarella, “The Development of Critical Thinking: Does College Make a Difference?” Journal of College Student Development 30:1 (January 1989): 19-26.

- See John E. McPeck, “Stalking Beasts, but Swatting Flies: The Teaching of Critical Thinking,” Canadian Journal of Education 9:1 (Winter 1984): 28-44; and __________, “Critical Thinking and Subject Specificity: A Reply to Ennis,” Educational Researcher 19:4 (May 1990): 10-12.

- Christopher R. Huber and Nathan R. Kuncel, “Does College Teach Critical Thinking? A Meta-Analysis,” Review of Educational Research 86:2 (June 2016): 431-468.

- Lisa Tsui, “A Review of Research on Critical Thinking” (1998): https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED427572.pdf. Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Miami, Florida, November 5-8, 1998. Tsui reviewed research from a total of 62 studies measuring the growth of critical thinking. Findings showed gains in critical and higher-order thinking skills during the college years. See also James H. McMillan, “Enhancing College Students’ Critical Thinking: A Review of Studies,” Research in Higher Education 26:1 (1987): 3-29.

- The self-esteem movement in American schools during the 1980s and 1990s emerged from the work of John Vasconcellos, a California senator, and the California Taskforce to Promote Self-Esteem and Personal Social Responsibility. See “Toward a State of Esteem. The Final Report of the California Task Force to Promote Self-Esteem and Personal and Social Responsibility” (January 1990): https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED321170.pdf. Some educational researchers have compared it to the current social and emotional learning (SEL) movement. See the work of Chester E. Finn, “The Social-Emotional-Learning Movement and the Self-esteem Movement,” Education Next (July 2017):https://www.educationnext.org/social-emotional-learning-movement-self-esteem-movement/.

- There continues to be a global emphasis on the impact of critical thinking in higher education. See, for example, Elizabeth Tofaris, Tristan McCowan, and Rebecca Schendel, “Reforming Higher Education Teaching Practices in Africa.” A series paper published by the ESRC-DFID Research Impact, Cambridge, U.K.: REAL Centre, University of Cambridge and The Impact Initiative (March 2020): https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/15197; Shoko Yoneyama, “Critiquing Critical Thinking: Asia’s Contribution Towards Sociological Conceptualization,” in Bridging Transcultural Divides: Asian Languages and Cultures in Global Higher Education, Xianlin Song and Kate Cadman, eds. (Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide Press, 2012), 231-250; Caroline Dominguez and Rita Payan-Carreira, eds., Promoting Critical Thinking in European Higher Education Institutions: Towards an Educational Protocol (Vila Real, Portugal: Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, 2019).

- The most frequent topic for quality-enhancement plans (QEP) within the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) accreditation region is critical thinking. See https://sacscoc.org/.

- The National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) defines career readiness as the attainment and demonstration of requisite competencies that broadly prepare college graduates for successful transition into the workforce. These competencies of Critical Thinking/Problem Solving help the individual “[e]xercise sound reasoning to analyze issues, make decisions, and overcome problems. The individual is able to obtain, interpret, and use knowledge, facts, and data in this process, and may demonstrate originality and inventiveness”: http://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/.

- Martha L. A. Stassen, et al. discuss the impact of academic disciplines on critical-thinking definitions. See Judith E. Miller and James E. Groccia, eds., To Improve the Academy: Resources for Faculty, Instructional, and Organizational Development (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2011), 127.

- Pew Research Center, “Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change” (February 2010): https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/.

- Ellen G. White, Messages to Young People (Washington, D.C..: Review and Herald, 1930), 260.

- Ibid.

- Ellen G. White, Education, 11.

- Richard Paul and Linda Elder, The Thinker’s Guide to Understanding the Foundations of Ethical Reasoning: Based on Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools (Tomales, Calif.: The Foundation for Critical Thinking, 2006). See also http://www.criticalthinking.org.

- Ellen G. White, Christian Education (Battle Creek, Mich.: International Tract Society, 1894), 58.

- __________, Fundamentals of Christian Education (Nashville, Tenn.: Southern Publishing Assn., 1923), 374, 375.

- __________, Education, 16-18.

- __________, The Adventist Home (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald, 1952), 414.

- Findings from the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) study on student spirituality can be accessed at: http://spirituality.ucla.edu/.

- New International Version (NIV). Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

- Leslie N. Pollard, “Restoration: The Mission of Adventist Higher Education,” Adventist Review (September 4, 2016): 38: https://www.adventistreview.org/1609-36.

- Ibid., 39.

- Deril Wood and Jeannette Dulan, “Inquiry Teaching in Higher Education: A Critical-thinking Context,” The Journal of Adventist Education 78:3 (February/March 2016): 45-51: circle.adventist.org/files/jae/en/jae201678034507.pdf; In L. M. Brown’s General Philosophy in Education (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966), the author argued that the tools of critical thinking are meaning, arguments, inferences, implications, knowing, theories/principles/laws, viewpoint, and evaluation. In Gerald Nosich’s Learning to Think Things Through: A Critical Guide to Thinking Across the Curriculum (New York: Pearson, 2012), 11 elements for critiquing one’s discipline are identified: purpose, question at issue, context, information, assumption, conclusion, implications and consequences, point of view, concepts, conclusions and interpretations, and alternatives (96, 97).

- White, Education, 30.

- __________, Our High Calling (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald, 1961), 16.

- In Our High Calling, Ellen G. White wrote: “Christ, His character and work, is the center and circumference of all truth. He is the chain upon which the jewels of doctrine are linked. In Him is found the complete system of truth” (16).

- In her address to the 1909 General Conference Session, Ellen G. White challenged all Adventist education—higher education included—with a one-question test: “Is it fitting us to keep our minds fixed upon the mark of the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus?” (“A Lesson in Health Reform,” Advent Review and Sabbath Herald 87:6 [February 10, 1910]: 7).

- See John 1:17; 16:13.